Summary

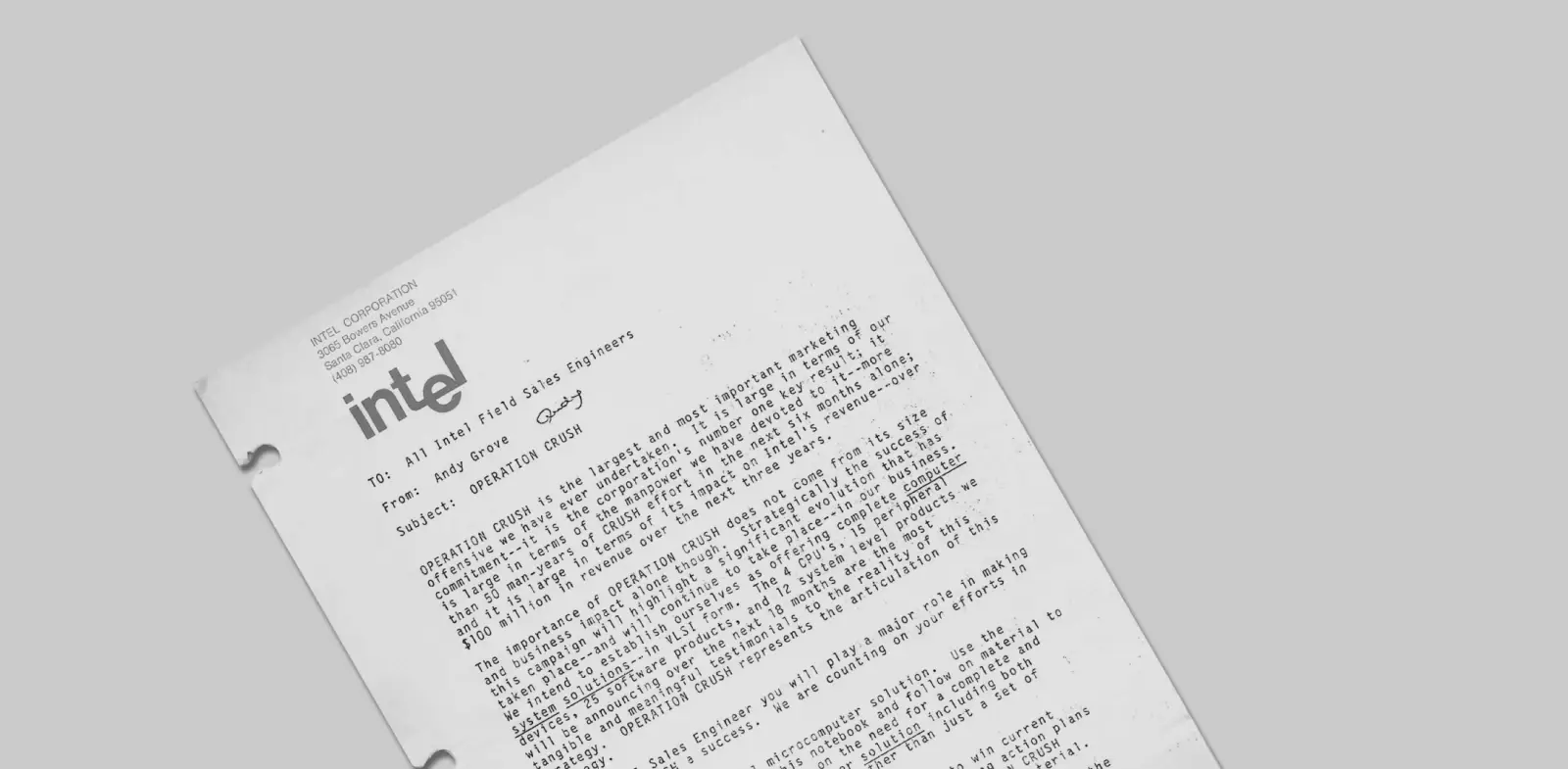

Early in his career, Andy Grove, the father of OKRs, had seen how valuing expertise without execution could lead to mediocre outcomes. When he joined a fledgling company called Intel, he knew he needed a management method that would transform the way teams worked. So he developed one—a radically different approach that changed not only Intel but other organizations for decades to come.

A crackly video opens to hushed murmurs and shuffling papers in a classroom as a wiry man with curly hair (tie, no jacket) strides resolutely up to a projector. He speaks, and two aspects of his personality emerge almost instantly: a focused determination that says he means business, and a loose humor that comes from someone who enjoys corralling smart people into a room, just to see what happens.

But this is no schoolteacher; he’s Andy Grove, the father of management science. Among his many seminar students over the years was John Doerr, who would on to use Grove’s methods to revolutionize the way companies like Google and Apple are run, and eventually to write a book about the process, Measure What Matters.

Born András István Gróf in Hungary in 1936, Grove survived the Holocaust by taking on a false identity, reaching America with little English and no money. He joined a fledgling company called Intel and transformed it using his management method, known as OKRs, or Objectives and Key Results.

Grove presided over Intel’s move from memory chips to microprocessors, increasing the power and decreasing the cost of the PC, setting in motion a process that would put personal computers in 95 percent of American households by 2024, and make smartphones ubiquitous. Under Grove, Intel increased revenues from $1.9 billion to $26 billion. None of this would have been possible without OKRs.

OKRs didn’t come out of nowhere. At Grove’s previous company, he had seen how valuing expertise without execution could lead to mediocre outcomes. He needed a radically different approach, and he found it in the work of Peter Drucker, who had introduced MBOs, or Management by Objectives, in the 1950s: a precursor to the idea that we do our best work when we’re focused on results, not simply on looking busy.

OKRs overturned the top-down management system. Suddenly, workers were valued by what they accomplished, not by their background, degree, or title. With OKRs, execution is more important than mere ideas, and Grove, who had fought his way out of Communist Hungary to become Time Magazine’s “Man of the Year,” was living proof of this. As one Intel historian put it, “He was sort of a walking OKR.”

Grove’s assertion that workers could be responsible for setting their own goals, and that every member of a company counts, from C.E.O. to intern, was something he practiced, not just preached. A man described as warm and empathetic, but also demanding and exacting, Grove was determined to help people help themselves.

Today, Doerr has taken up this mantle, earning the nickname “Johnny Appleseed of OKRs.” He introduced the philosophy to Google’s founders in 1999, and has inspired nonprofits like the Gates Foundation and schools like the Khan Lab School.

Now everyone, from Larry and Sergey to kindergarteners, is using OKRs to reach new heights. As Grove put it, “It almost doesn’t matter what you know. It’s what you can do with whatever you know.” In other words, with great power comes great responsibility. Spoken like a true superhero.